Carbon ‘rainbow’: Unilever pledges $1.2B to scrub fossil fuels from cleaning products

Cecilia Keating

Tue, 09/08/2020 – 00:15

Unilever last week revealed plans to funnel close to $1.2 billion over the next 10 years into initiatives that will allow it to replace chemicals in its cleaning products made from fossil fuel feedstocks with greener alternatives — an investment it described as critical to meeting its aim of achieving net-zero emissions from its products by 2039.

The new program, Clean Future, is largely focused on identifying and commercializing alternative sources of carbon for surfactants, the petrochemical molecules found in cleaning products that help remove grease from fabrics and surfaces. More than 46 percent of Unilever’s cleaning and laundry products’ carbon footprint is incurred by chemicals made from fossil fuel-produced carbon, most of which are used in surfactants.

However, the firm now intends to explore, invest and ramp up carbon capture and use technologies that will eliminate the need for fresh carbon feedstocks and instead allow it to tap recycled carbon already on or above ground, for example, through captured carbon dioxide or carbon captured from waste materials.

Peter Styring, professor of chemical engineering and chemistry at the University of Sheffield, who has partnered with Unilever on the initiative, explained to BusinessGreen that Unilever’s investment could help catalyze a transition away from fossil fuel-derived petrochemicals, a lesser understood but necessary element of the move towards a net-zero emissions economy.

“The move from fossil fuel is mainly associated with an energy transition. but similarly we need to look at a transition away from fossil fuel-derived petrochemicals,” he said. “The work we are doing is to try and replace existing chemicals within the supply chain, with not necessarily new chemicals but chemicals derived from a different supply.”

Through a strategic partnership with Unilever, Styring’s team at the University of Sheffield is working to identity and develop the technologies that will allow the firm to divorce itself from chemicals made from fossil fuel feedstocks, a transition the multinational anticipates will reduce the carbon footprint of its laundry and cleaning products by as much as 20 percent.

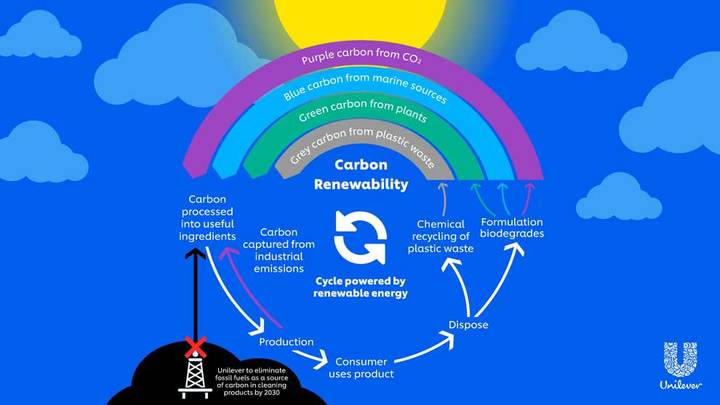

In an attempt to help consumers, competitors and partners understand its plans and the production processes behind the technologies it plans to explore, Unilever has devised a “carbon rainbow” model that outlines the alternatives to fossil fuel-produced carbon. On the carbon rainbow, carbon produced through captured carbon dioxide is dubbed “purple carbon”; plants and biological-sourced carbon is labeled “green carbon”; marine-sourced carbon is branded “blue carbon”; and waste material-sourced carbon is denoted as “grey carbon.” Conventional fossil fuel-derived carbon is simply known as “black carbon.”

Styring, a carbon capture and use expert, suggested that eliminating petrochemicals across industry will require active pursuit of all “shades” of the rainbow.

“There is no silver bullet; nothing is going to cure the climate issue on its own,” he said. “There has to be a cooperative effect between different technologies. I would love to say purple carbon will be the No. 1 technology, but I can’t because at this stage I don’t know. It really will be a balance and the other shades on the rainbow have to be taken into account.”

Unilever’s Clean Future program specifically will focus on funding biotechnology research, CO2 use and low-carbon chemistry, as well as biodegradable and water-efficient product formulations. It already supports a number of initiatives that aim to slash the environmental impact of the firm’s cleaning and laundry products.

For example, in Slovakia, the company is working with biotechnology company Evonik Industries to develop the production of rhamnolipids, a renewable and biodegradable surfactant used in its Sunlight dishwashing liquid in Chile and Vietnam. And in Southern India, Unilever is sourcing soda ash — an ingredient in laundry powders — from CO2 capture technology. The firm expects to scale up the use of both technologies over the years to come.

Meanwhile, liquid detergent made by Persil — one of Unilever’s largest and most popular brands in the United Kingdom — has been reformulated to rely on plant-based stain removers, with the new line expected to reach British supermarkets later this month.

However, beyond the impact on Unilever’s product lines, Styring is hopeful Unilever’s commitment to pour $1.2 billion over 10 years into purging fossil fuel-derived chemicals from its laundry and cleaning products will have a major impact on improving public understanding of the role of environmentally damaging petrochemical feedstocks.

“The carbon dioxide utilization industry is developing, and over the last 10 years there have been a lot of development, but it tends to be in niche industries that the public don’t really see — the production of ethanol and methanol and various chemicals,” he explained. “This is a chemical — or a series of chemicals — that goes into households around the world. This will have a big impact.”

Unilever has committed to spend a part of its $1.2 billion pot to support the development of “brand communications” that explain the various new technologies to customers.

Perhaps even more crucially, Styring reckons the new investment has the potential to accelerate the commercialization of renewable and recycled carbon feedstock technologies that so far largely have been confined to research departments around the world.

“What will happen with these strategic partnerships is that you can identify which tech are going to be world-leading, and you can put investment into these in a way that a research council can’t,” he predicted. “Because ultimately you are looking for a commercial success, a product that will give you a profit and at the same time reduce environmental impact. So I think the investment Unilever is making here will accelerate these technologies and allow them to move from small scale, bench scale and small laboratory scale and target a much better commercial operation.”

His team, for example, will be working with Unilever to investigate how different technologies can be clustered together to form a local ecosystem that can produce alternatives to black carbon at scale.

The move from fossil fuel is mainly associated with an energy transition. but similarly we need to look at a transition away from fossil fuel-derived petrochemicals.

“At the moment, the emphasis will be location, location, location,” Styring said. “Have you got the energy to do the chemistry — energy in terms of renewables — do you have the carbon dioxide readily available, do you have hydrogen and water readily available, do you have the inorganics?”

Carbon use can be developed at major existing sources of carbon dioxide such as power stations and heavy industrial plans, and could be ramped up within a “couple years,” Styring suggested. In contrast, more ambitious projects focused on direct air capture (DAC) could prove effective but will require much more time and money to reach commercial viability.

That said, Styring is still enthusiastic about the long-term prospects for DAC as it is ramped up, predicting its impact could prove to be “phenomenal.” DAC technology also has one big potential advantage over conventional carbon capture systems: It is not tied to a particular location and as such would give operators the ability to tap carbon from the air for their products anywhere in the world, eliminating the need for complex and costly transportation infrastructure and supply chains to ferry the captured carbon to production sites.

Styring is hopeful that Unilever’s commitment will encourage the government to throw its weight behind carbon capture and use, a field where he believes the U.K. could emerge as a world leader.

“When you go to [carbon capture use] conferences, the U.K. is always the highest represented nation outside of the organizing nation,” he observed. “But the funding doesn’t reflect this, in terms of government funding. Germany is by far and away the biggest funder of this type of research. We have the opportunity to use the best British science and engineering, and psychology and supply chain management. … We have the opportunity to make Britain a leading force, but it needs that investment.”

Styring said he has been pressing the government to divert a portion of the subsidies it funnels into oil and gas into carbon capture and use technology designed to produce petrochemicals and produce fuels.

The government would argue that it has been listening and plans are progressing — albeit slower than campaigners would like — for new net-zero clusters that could deploy a range of carbon capture use and storage clusters at industrial sites across the U.K. The wide-ranging implications that would flow from such hubs could prove to be hugely significant, providing the fossil fuel industry with both a means to decarbonize and new markets for its capture carbon.

At the same time, advances in green and blue carbon could slash demand for fossil fuels at a time when oil majors are betting on the petrochemicals market to pick up some of the slack as the transition to electric vehicles gathers pace. Unilever’s $1.2 billion investment could yet have a huge impact far beyond the consumer goods market.

Innovation

Bio Economy